India has cricket. The Welsh worship rugby. Baseball was the American pastime, but the Dominicans and Japanese now bat above the Red/White/Blue. Here in Serbia and in the rest of the former Yugoslavia, the physical culture has been taking on the global athletics scene across football, basketball, and tennis. At home and in diaspora, surnames ending in -ić are out and proud on pitches and courts! When Sasha was growing up, his family made a point of buying tickets for sports teams starring Yugoslavian athletes, and there were plenty to cheer on from the stands of sports stadiums across Southern California. With cable and streaming, games are broadcast right to us, and there are plenty of teams and athletes for residents of the Balkans to have on their respective radars.

Getting to Know YU: The Footballers

Yugoslavia (Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes/Kingdom of Yugoslavia/Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia) made its debut at the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium, a new country on a continent battered by the Great War. 64 years later, the rebranded SFRJ hosted the Winter Olympics in Sarajevo, the city where the political intrigue that led to WWI unfolded. In the interim, the Yugos came in third in the 1930's World Cup, held in Montevideo, Uruguay. The 2010 Serbian film Montevideo, God Bless You! is based on the first Yugoslav football team who made this journey to South America to represent their young, eager nation.

Football (as in soccer football) was popular in Austria-Hungary, so by the 19th century the sport had filtered into the empire’s South Slavic sphere. The 1920-30s saw the sport grow, with local teams formed alongside a national team. Two rival teams, FK Partizan and FK Red Star (Crvena Zvezda), both based in Beograd, the federal capital, emerged and remain one of the fiercest football rivalries in the world.

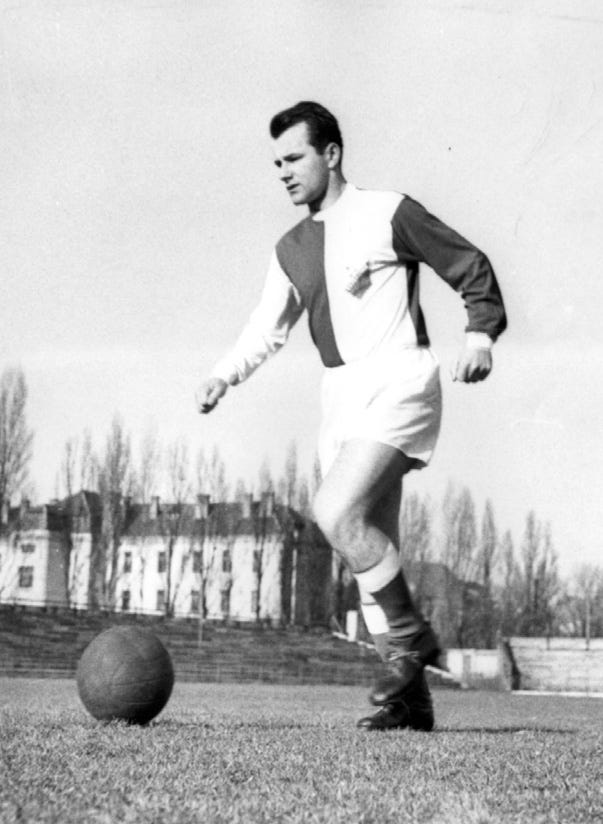

After WWII, Yugoslavia rebuilt itself, split from the Warsaw Pact, and made its way as a non-aligned nation with big public investment in all things athletics. Without the restrictions of the Eastern Bloc, Yugoslav national players were obligated to “play for the people” until the age of 28, after which they were free to go abroad and compete in Western Europe’s affluent clubs, beckoned by big money and fame. Born in 1931, Vujadin Boškov, was one of the first Yugoslav players to make an international name for himself. Raised in northern Serbia outside Novi Sad, he devoted fourteen years to FK Vojvodina, and went on to play midfield for Yugoslavia in the 1952 Olympics, helping the team take home the silver medal before competing in the 1954 and 1958 World Cups.

He joined the Serie A team Sampdoria in 1961 and then moved to the Young Fellows of Zurich, where he wrapped up his career as a player. Trading his boots for a suit, his managerial tenure included running Yugoslavia’s national team, as well as leading Real Madrid, Zaragoza, Roma, Napoli, and his old club, Sampdoria.

European clubs continued to pull the cream of the crop ex-YU players. The late Siniša Mihajlović and the breathing Robert Prosinečki of 1991 Red Star Belgrade victory played for Inter Milan and Real Madrid/Barcelona respectively, paving the way for an ongoing eastern stream for Serie A, La Liga, EPL, and Bundesliga that is still going strong in 2024. Red Star’s other rival (bedsides Partizan) was Dinamo Zagreb, a team famous for rejecting both Mihajlović (the virtuoso of free kicks refused to cut his hair) and Prosinečki (they did not recognize his talent).

Dinamo was the first team of Croatian-born Zvonimir Boban, who made a name for himself in Italy’s Serie A following a 1990 brawl with police during a Red Star vs. Dinamo match that put his name on the map. The Red Star Class of ‘91 also included Dejan Savićević, who, like Boban, ended up being recruited by AC Milan. Mihajlović joined rival Inter Milan in 2004 after stints with Roma, Lazio, and Sampdoria, alongside compatriot and fellow former Lazio player Dejan Stanković. The two would remain lifelong friends, with Dejan acting as pallbearer when Sinisa lost his battle with leukemia in December 2022.

Red Star Belgrade’s 1991 Euro Cup victory holds a special place for us, since Sasha watched this game live at TC’s in San Pedro back in 1991. To see his grandfather’s favorite team win such an important championship as his family’s country tread on stormy political waters was monumental for young Sasha, and although a drive-thru Starbucks occupies the spot where TC’s used to be, he treasures that spot on 9th and Gaffey Sts. to this day.

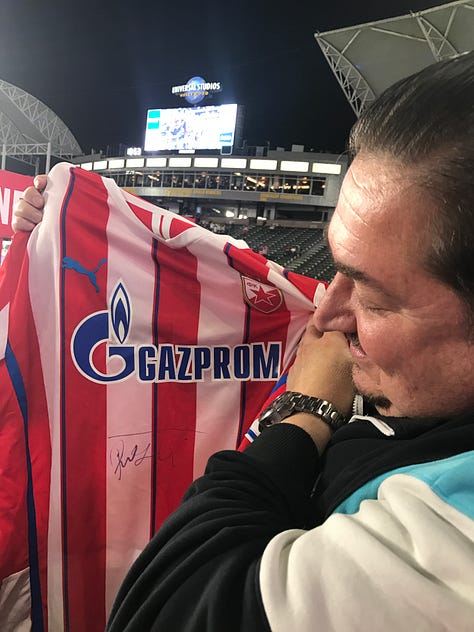

Politics marred the lives of that winning team’s members. Both Mihajlović and Prosinečki had mixed Serbian and Croatian parentage, and as Yugoslavia disintegrated, their families’ were in harms way. Each faced nasty words from extremists on different sides who bad-mouthed these champions for having mixed heritage. Despite ugliness from haters, both ballers continued their international careers and remain loved by football fans across the Balkans. In 2018, Prosinečki was coaching Bosnia’s national team, which traveled to SoCal to play a friendly against the LA Galaxy. One of Prosinečki’s number one fans was waiting in stands before the game started, along with his wife (who packed a Sharpie marker and a Red Star jersey). Said wife waved the jersey and the marker, and over came Prosinečki to sign the jersey, bringing Sasha full circle with his childhood sports icon.

On the front of the younger generation, Croatian Luka Modrić made his mark on the EPL playing for Tottenham Hotspur before going on to becoming La Liga royalty with Real Madrid from 2012 to the present. Modrić the midfielder led Croatia’s national team to the World Cup finals in 2018, losing to France in the final match. Manchester United’s first foreign-born captain was Serbian Nemanja Vidić, a player who “puts his head where other players are scared to put their feet.” As Vidić worked the ball on the pitch, packs of Red Devil hooligans sang from the stands: “Nemanja, wo-ah. He comes from Serbia. He’ll f***in’ murder ya!”

Vidić, known to friends as Vida, remarked to a reporter that he despite his aggressive style of play, he was never out to hurt or kill: “I play strong, yes. But I am not a dirty player and I am not a killer, as the fans sing. I don’t want to hurt or injure anyone. I just want to win.” Vida got himself beat up more than he whooped others, breaking his nose, collar bone, wrist, and hands before retiring in 2016 after a series of nasty concussions, back injuries, and a hernia. Modrić, on the other foot, retired from Croatia’s national team, but is still looking to prolong his professional club career as he spent the spring of 2023 in Beograd undergoing treatment with a renowned sports medicine doctor!

Basket Cases

Yugoslav basketball gained traction in the post-WWII period, launching to prominence in 1963 and remaining on top of the European championships until 1992. 1988 saw the Yugoslav national team took silver at the Seoul Olympics after having beaten the US team at the FIBA U19 World Championships the year before. Thus 1988 was the year that Sports Illustrated declared: “The Yugos Are Coming.”

Prominent YU basketball players included Vlade Divac, Drazen Petrović, and Toni Kukoć. Divac made a name for himself on the Lakers, with support from local zemljak (countrymen) in the LA area, including Sasha’s dad joined by the rest of their family. Petrović signed with the Portland Trailblazers, while Kukoć made it to the American Midwest with the Chicago Bulls. Political tensions at home strained these friendships forged on winning courts, and Petrović’s 1993 death in a car wreck meant he and Divac never had a chance to reconcile. ESPN did a great documentary on the rise and strains of Yugoslav basketball back in 2010 called Once Brothers, focusing on Divac and following the personal, professional, and political forces that impacted the Balkan basketball culture that came to global attention from the 1980s onward.

Rebounding to win the world basketball championship as a contracted country in 2002, Yugoslavia beat the US on its home turf before that national name disappeared from the map to become Serbia-Montenegro, then later (just) Serbia. New borders aside, the (ex) Yugos still had many more to send!

Today’s NBA courts are pounded by Serbian players Nikola Jokić, Boban Marjanović, Bogdan Bogdanović, Aleksej Pokuševski, Nikola Jović, and Vasilije Micić, as well as Montenegrin Nikola Vučević. Luka Dončić, with Serbian and Slovenian heritage plays for Slovenia alongside Vlatko Čančar; plus brothers Goran and Zoran Dragić.

From Croatia, the NBA has Bojan Bogdanović, Dario Šarić, Ivica Zubac, and Luka Šamanić, and from Bosnia comes Jusuf Nurkić. Agent extraordinaire, Serbian-born Misko Raznatović, continues to represent all these basketball stars from the former Yugoslavia, ensuring they negotiate the most advantageous contracts.

Interestingly enough, it was Vlade Divac, former Lakers star and Sacramento Kings general manager, who failed to pick Mavericks star Dončić during the 2018 draft season. Vlade apparently had nothing against young Luka, but back in the old country, Dončić’s father and Vlade didn’t jibe on the Yugoslav national team. It ended as a bad move for Vlade, since Luka succeeded in Dallas while Vlade’s dupe draft faltered in Sacramento. This failure led to Divac’s loss of his GM job (and probably lots of gloating from the Dončić Sr.). As a Californian, I must admit I am a little ticked that we lost Luka to Texas. Sasha shares similar sentiments, despite his enduring friendship with Vlade. :(

Last month Northern California and the entire basketball world said goodbye to Dejan Milojević, a Belgrade native and assistant coach for San Francisco’s Golden State Warriors. Milojević represented Yugoslavia-to-Serbia-and-Montenegro as a national player, and joined the coaching staff of the Warriors back in 2021. He is remembered affectionately for his mentorship of young players, in both Eastern Europe and the US, and for his work alongside fellow Serb Igor Kokoškov, the NBA’s first foreign coach who now works with the Atlanta Hawks.

Backhanded

Tennis took some time to gain traction in Yugoslavia, but by the late 1960s, an exceptional player-turned-coach named Jelena Genčić built the foundation for the sports’ success in the country and its successor republics. Genčić excelled in both handball and tennis, but chose to focus on the latter exclusively from 1968 on.

She served as the president of the Partizan Club tennis division before taking on the role of captain in Yugoslav Tennis Association Juniors’ (league), training and traveling with the nation’s leading young tennis prodigies. Monica Seles and Goran Ivanišević honed their early skills under her care, while Genčić worked to secure funding and high-quality facilities across Yugoslavia to ensure her charges had top-notch amenities at their disposal.

Young Monica Seles and Goran Ivanišević trained with Genčić, who once had to discipline young Goran for ripping the head off a plastic doll that Monica brought on tour. Monica Seles would go on to become the youngest winner of the French Open in 1990. Seles was the victim of a stabbing in 1993, but she rebounded to show the world that a blade narrowly missing her spinal cord was not going to hamper her unapologetic talent.

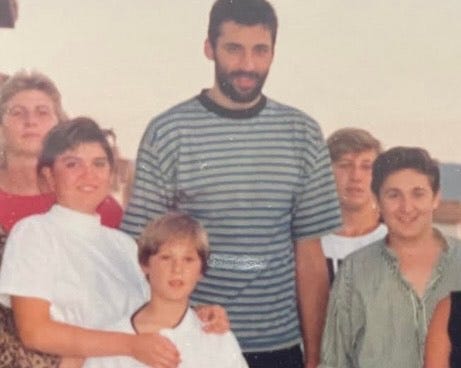

In the summer of 1991, Genčić noticed a little boy watching her coach tennis clinics at the mountain resort of Kopaonik. After Genčić saw him watching from the sidelines over the course of several weeks, she invited him on court, learned his name was Novak, and asked if he wanted to try taking a swing with a racket.

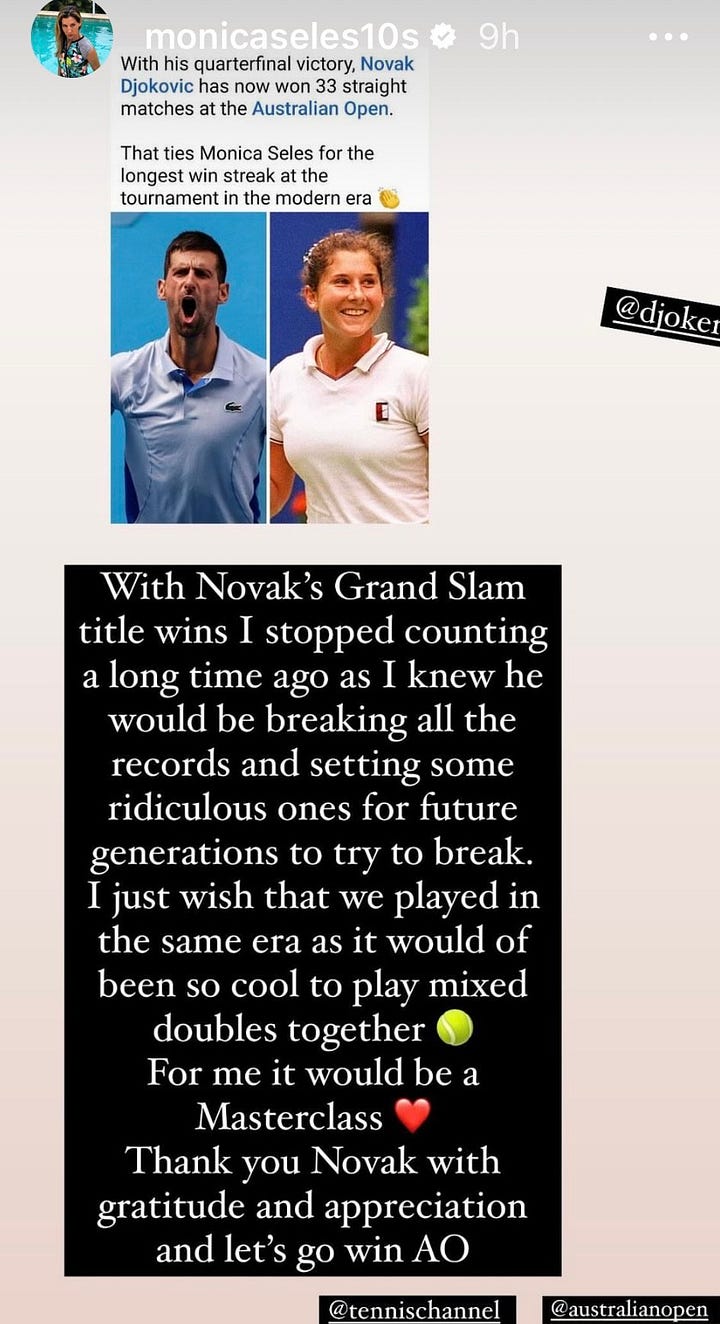

Many serves and broken rackets later, Novak Djokovic reigns as the sport’s GOAT. In 2019, Djokovic appeared on stage to accept an award from Seles, whom he grew up idolizing as one of the proteges of their mutual “tennis mother” Jelena Genčić. Genčić passed away in 2013, but today on social media, two of her legacies continue to support one another across time and space, while Ivanišević, Nole’s coach, is never far off court.

While Nole battled opponents down in Melbourne at this year’s Australian Open, ex-YU tennis has many notables, like the characters below!

Diaspora Moves

Starting in the 1960s, Yugoslavian guest workers and professional recruits made their way to Western Europe, North America, and Australia. Sweden, a country known for its hockey prowess, landed on the football map with a slew of players Swedish by birth, but Yugoslav by heritage. Gothenburg is home to Teddy Lucić, son of a Croatian father and Finnish mother. He made his debut for the Swedish national team in 1995, going on to stints in Serie A (Bologna), EPL (Leeds), and Bundesliga (Bayer Leverkusen). Over in the Stockholm suburbs grew Daniel Majstorović, the son of Serbian parents. He played centre back for his local club, before moving on to teams in Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland before returning home to play for Malmö FF, a team made famous by another Yugo-Viking player with sharp skills and an infamous temper. Majostorović’s last stints were with Celtic in Scotland and on transfer for AEK Athens, were his abilities shone but his knees gave out.

Down south in Malmö, the son of a Croatian mother and Bosnian father was developing a reputation for football flair in the city’s low-income community of Rosengård. His attitude flew at FK Balkan, a local club for the children of Southeastern European immigrants, but landed him in hot water at Malmö FF, where his abilities grew and he was known by his first name, Zlatan, meaning “golden” in Serbo-Croatian. Zlatan was bought by Ajax, the Netherlands’ top team, where in 2004 he dribbled across the field in a series of moves that landed the team a winning goal and the player a shot in Serie A with Torino team Juventus. By the time he wrapped with Ajax, his jerseys were emblazoned with his full surname, Ibrahimović, the name under which he went on to score for seven different teams in the Champions League, conquer the American MLS, and bicycle kick a ball over forty meters into a pitch for Sweden’s national team.

These original -ić’s are now retired, but a new generation of players with Balkan blood are on the rise in Scandinavia. Notables include Dejan Kulusevski, Zećira Mušović, Armin Gigović, Zinedin Smajlović, David Čelić, Emin Hasić, Allen Smajić, and of course, two heirs to a dynasty, Maximilian and Vincent Ibrahimović. And although Majstorović retired from the pitch over a decade ago, he now serves as the head of football recruitment for Scandinavia’s leading sports management agency, Wesport.

The “bad boy” of Austrian football, Marko Arnautović, was born to an Austrian mother and Serbian father in a suburb of Vienna. Arnautović and fellow Austrian-Serbs Saša Kalajdžić and Aleksandar Dragović were called up to the alpine republic’s national team, which recently added Dejan Ljubičić, Austrian with Bosnian-Croatian parents. On the Swiss side, Dusan Pavlović paved the way for first-generation Swiss players back in the 1990s, playing over 100 games with 8 different teams across the Swiss Super League. Josip Drmić played in Switzerland, where he was born, but took up dual citizenship to play for Dinamo Zagreb later in his career. Today, Filip Ugrinić plays for the national team, as well as with Bern’s Young Boys, while Miloš Veljković is Swiss-born, but as a dual citizen, is able to play for Serbia’s national after getting his start in club sports with FC Basel.

North America is home to a lower concentration of ex-YU descendants, but a few have made names for themselves with their physical prowess. “Pistol” Pete Maravich, born in Pittsburgh of Serbian heritage, followed in his father’s footsteps by taking up basketball. He played at the collegiate level for LSU, went pro with the Atlanta Hawks, and joined the Jazz while the team was still located in its birthplace of New Orleans. He made the move to Utah with the Jazz, but spent his last year of professional playing in Boston for the Celtics. Injuries forced him to retire in 1980, and poor health followed until 1988, when heart failure caused by a congenital defect took his life. He was only 40 at the time of his passing, but his short life was a legendary one as he remains one the highest scorers in college basketball who went on to shape the NBA game as we know it today.

Another Boomer gen. basketball name is Greg Popovich, who was born in Chicago to a Serbian father and Croatian mother. He served in the US Air Force before entering the world of basketball coaching. He pivoted from the San Antonio Spurs to the Golden State Warriors, and back again to the Spurs, where he remains the head coach.

Football-soccer opportunities are more meager in North American than they are in Europe, but a few notables stand out from the Yugoslav diaspora who took on both American soccer and made the transition to the more competitive realm of European football. Two notable players of American nationality with Balkan heritage who made the transitions from US training to European clubs were Jovan Kirovski and Sacha Kljestan. Kirovski was born in San Diego to Macedonian parents, and wound up on the youth team of Manchester United, where he was mentored by the legendary Scottish coach Sir Alex Ferguson. Kirovski played for Borussia Dortmund, Fortuna Köln, Sporting CP, Crystal Palace, and Birmingham City before returning to the US to play for the Galaxy before moving on to become the LA club’s technical director. While Kirovksi was playing in Europe, young Sacha Klejstan of Huntington Beach tacked up a poster of him (Kirovski) on his bedroom wall for motivation. Before arriving in the LA area, Sacha’s father Slavko played for FK Željezničar Sarajevo. When he arrived in the port town of San Pedro and placed a pay phone call to a contractor’s office to inquire about a job, the construction company owner who answered recognized his name from the Sarajevo team roster. Klejstan Sr. landed the job and a green card, while his American-born son Sacha completed a five-year stint with Belgian team Anderlecht before coming home to the MLS for the New York Red Bulls, Orlando City, and the LA Galaxy, where he works alongside his childhood idol, Kirovski.

When Michael Phelps was reigning in the world of swimming, Milorad Čavić was Another first generation Southern Californian Čavić opted to swim for his parents’ home country. A graduate of UC Berkeley, Čavić took gold for Serbia-Montenegro in the 100m butterfly, setting a new record in 2003. By 2008, the 50m championship in butterfly stroke was his at the European championships and when the August 2008 Olympics rolled around, he was ready to take on Phelps. He finished first in the preliminaries, but in the final round Phelps was ruled the winner because despite Čavić arriving first, Phelps applied more force to the electronic touchpad by the milliseconds. Hmm, not sure that is a fair way to calculate a victory…

Fast forward to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and in came Anastasija “Ana” Zolotić, representing Team USA in women’s taekwondo. Born in Florida and trained in Colorado, she was raised by Bosnian-Serbian parents. Her father had been a competitor in Yugoslavia’s martial arts scene back in the 1980s, and introduced his daughter to the Korean art of high, swift kicks when she was in kindergarten. The COVID pandemic limited the audience who could watch Zolotić live as she kicked down Russia’s Tatiana Minina. Shortly after, Ana underwent knee surgery, having competed on her literal last leg to score Olympic gold, becoming the first American woman and youngest ever female martial artist to do so!

Now and Then

After Slovenia was hit by catastrophic flooding in late summer 2023, a charity match to raise money for the victims was organized at the behest of Slovenian-born EUFA president Aleksander Čeferin. Personal phone calls connected players from the former Yugoslavia, as well as numerous international stars and players with diaspora heritage from three generations of footballers YUnited to raise money. This crew included Nemanja Vidić, Zlatan Ibrahimović, Zvonomir Boban, Predrag Mijatović, Vedran Ćorluka, Milivoje Novaković, Davor Šuker, Boštjan Cesar, Miran Pavlin, Branko Ilić, Aljoša Asanović, Milenko Aćimović, Mišo Brečko, Bojan Jokić, Robert Koren, Dejan Savičević, Mario Mandžukić, and Ivica Olić. Footballers spanning the different republics across three generations who all came together amidst roaring crowds, united by their connection to a region where sports have sometimes served to divide, but have also had a greater power to unite.

The mindset of “You (YU) can do it!” is unrelenting on pitches, courts, and fields across the world. Sasha has spent years telling me that “his people” (ie. anyone from or with origins in the former Yugoslavia) make the best athletes in the world. I did not grow up with a family that followed any major team sports, so most of my knowledge of the sports world comes from Sasha’s passion for different games and athletes from the Balkan region. I’ve been listing to the stories and watching games absent-mindedly, yet even now I am astounded by just how prolific this small corner of the world has been in producing world class athletes.

The region is also known for its successes in lesser profile sports like waterpolo and handball, circulating coaches and players around the world. Yugoslavia took gold medals in handball in 1972 and 1984, while Croatia followed this lead winning gold in 1996 and 2004. Serbia took Olympic gold in men’s waterpolo in back-to-back Olympics in 2016 and 2022. Slovenia’s Anze Kopitar led the charge for the LA Kings hockey team since 2006, keeping the team on puck with giants from colder climates.

Sports culture was off my radar growing up, but everywhere here in Serbia I am reminded just how powerful sports can be for a small country that has become so well-regarded for its roster of international talents. State subsidies across the former Yugoslavia are also incredibly valuable to young athletes, as this public support means the great talents can flourish regardless of familial financial limitations. Klenak is a small village, yet their football team is quality, and neighboring Šabac has a full stadium. I may not be playing any team sports, but all this buzz around athleticism has got me back on track with strength training. Next month, the Beograd’s Crvena Zvezda (Red Star)-Partizan derby is set to happen, the rivalry where passions and pyrotechnics fly. I might be hiding behind an umbrella, but YU can bet we will be there, and Sasha’s cheers will probably drown out the fireworks!

A brilliant, entertaining and informative article! I will send it to my father Boris!