Vlach Magic: History, Anthropology, and Popular Culture

The Vlach Track

Our container finally arrived, and we are busy unpacking everything we shipped from California. Shout out to the Serbian Consulate in Chicago for guiding us through this process! As for the US Embassy, another ZERO out of five stars!

Amidst customs clearance and boxes, the topic of the Vlach people came up via a song on the radio (thanks to Marina for explaining the origin of this particular tune). The Vlachi are one of many unique cultural groups residing in the Balkan peninsula. If you watch Vice Media, you might have seen the piece covering the association of the Vlach people with unique supernatural practices.

Vice often covers interesting topics, but whether or not Vice did the Vlach culture justice is debatable. However, “The Truth Behind Serbia’s Notorious Witchcraft Subculture” piqued public interest in the English-speaking world surrounding the Vlachi. The very fact that the presenter referred to Vlach folkloric rituals as “Eastern Voodoo'' in the first minute of the program raises some red flags (since Voodoo, or Vodou, is an actual Haitian religion with West African roots). Yet parallels to the Haitian creed are evident, as spiritual mediation and physical, goal-oriented rituals characterize both traditions half a world apart.

Slavic/Romance

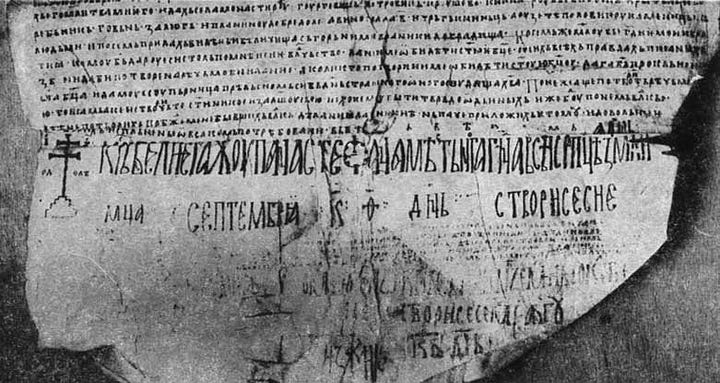

Like their neighbors, the Vlachi are historic members of the Orthodox Christian faith, with allegiances shifting between the Serbian and Romanian strands. They speak a language related to Romanian (Latin, or Romance-based), and in the past have been known as “Aromanians.” Byzantine records document Vlach presence in the region dating to the 9th century CE. The Romanian province of Wallachia has a common root with the word Vlach (or Vlachi), both coming from a Germanic exonym for the Balkan’s mountainous core. By the 12th century, the Serbian Nemanjic Dynasty included Vlach families in its founding charter, noting their occupational niche and membership in the community of Orthodox Christians. For the next two centuries, Serbian monarchs continued to grant deeds of land and legal recognition to Vlach residents within their realm, associating them with the Serbian church’s iconic monasteries at Žiča, Gračanica, Vranjina, Peć and Visoki Dečani. Vlach lands, with their numerous cave systems, were used by rebels fleeing Ottoman oppression during the five hundred years Turkish forces battled European militaries for control of the Balkan peninsula.

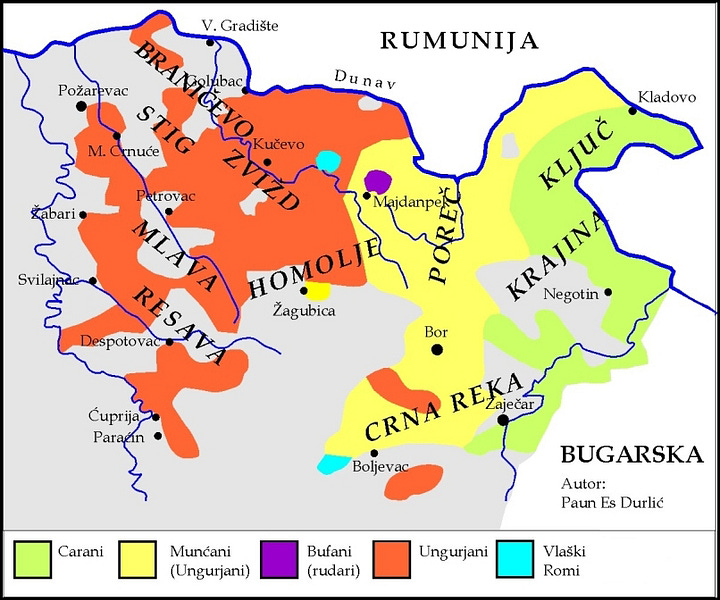

Pockets of Vlach people live in Romania, Hungary, Macedonia, Albania, and Greece, and smaller numbers previously lived in Croatia and Bosnia. Eastern Serbia, mostly the vicinity of the Timok Valley, is home to around 23,000 Vlachi. Not all speakers of Romanian dialects in Serbia are Vlach (some are ethnic Romanians living mostly in Vojvodina’s Banat), and Serbian Vlachi speak Serbian alongside Vlach. Politically-speaking, this raised issues with the Romanian government, who wanted Serbia’s Vlachi recognized as a part of the country’s Romanian minority. But the Serbian Vlachi view themselves as a distinct community, distinguishable from Serbia’s ethnic Romanians. The Vlach language was not standardized until recently, granting it official status as a minority tongue with an official dictionary. While some Serbian Vlachi have an affinity for Romania, most regard themselves as Serbian, largely thanks to their historical presence in Serbian society, plus the language and cultural rights they enjoy. Vlach music and folk dance are popular across Serbia, and many folk troupes perform at national and international festivals annually.

Eastern Serbia is rich with Roman archeological sites, as well as mountains, forests, and caves that inspire the (dark) imagination with natural beauty alongside the generational struggles against poverty and political instability experienced by the Vlachi. High unemployment in the post-Yugoslav years have meant a large exodus of young people from this area have moved west into larger Serbian cities, while others have sought opportunities abroad. So while the Vlachi are not a growing culture, they are an enduring one whose history is on the popular radar of people in Serbia and the broader Balkan region.

Of Vice and Vlach

So, what’s with the Vlachi and magic? Vlach culture, like many cultures in Eastern Europe, blends pre-Christian traditions with life in the Orthodox tradition. While men kept the churches, women kept the pre-Christian rituals at home and in the community as beliefs and rituals overlapped. Vice capitalized on this by meeting with ethnographers, who took their reporter to Eastern Serbia to meet up with “Babas,” or older women in the community. The Babas showcased fortune telling with kitchen table rituals and speaking about the past when soothsayers gathered by rivers and at the mouths of caves to hold seances.

The program host, Galeb Nikacevic, was royally roasted by Baba Ruza and Baba Desanka, who delivered more malice and less magic with a form of (mis)fortune real talk. These customs survive in the lives of the elderly and isolated, but to call them a subculture, as the program title does, might be an overstatement given that younger members of the Vlach culture have folded into mainstream society. Yet popular culture in both Serbia and abroad find fascination in the Vlach past.

Worlds Without End

Vlach magical practices exist, are a subject of anthropological interest, and some elders still dabble in it, with white magic associated with daylight rituals and benign wishes, while black magic is done by night with vengeful intentions. In 2007, a mass shooter in Jabukovac blamed his killing spree (and subsequent suicide attempt in the local cemetery on his parents’ grave) on a Vlach black magic spell, before being diagnosed with acute paranoid psychosis and committed to a state-run asylum. Historically, Vlachi believed that after death, a soul wandered for seven years before being admitted to the formal afterlife, and in the case of an engaged young man passing before his planned wedding, the funeral service needed to be converted into a wedding of sorts in which his fiancé was wed to his spirit, and required to spend at least one year “married” to his ghost. Relatives of the deceased often buried loved ones next to family homes, making generous offerings of food and spirits to support their dearly departed ones’ passages to an abundant afterlife.

In 2021, the now defunct “black wedding” reference was used as the basis for a Serbian television horror series by the same name (in Serbian: Crna Svadba). This series alludes to the 2007 mass shooting, connecting a real-life incidence of insanity-induced violence to late 20th century political upheaval and belief in the malevolent supernatural. Strahinja Madzarevic, who co-wrote the series with Nemanja Ćipranić, has also worked with Sasha, so this series is next on my watch list!

Land & Life

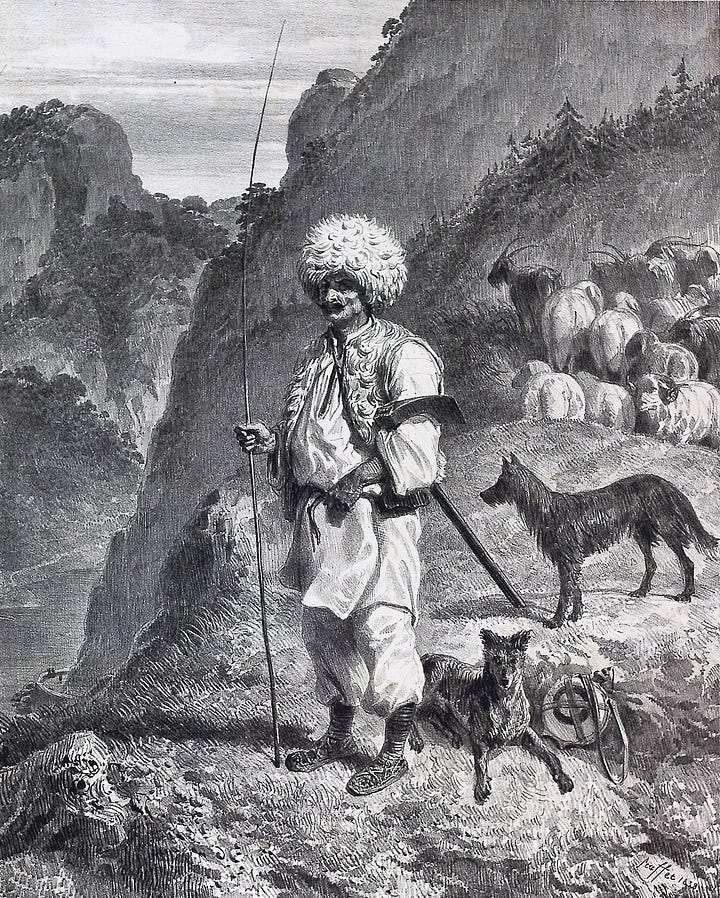

While magical rituals were and remain a part of Vlach culture, the occupation that has defined this community for centuries is less flashy, and more (literally!) fluffy. Professional pastoralism was the main hallmark of Vlach life, the occupational essence of their rural culture documented back in the Nemanjic dynasty’s 1198-1999 Hilandar charter. Vlach shepherds migrated with their flocks following the seasons, herding sheep and goats as far as the boundaries of Poland and Czechia. The Balkan peninsula, from the edges of Transylvania down into Greece, is known for its sheep and goat milk products, as well as its high caliber wool, making Vlach pastoralism a key component of the region’s traditional diet and textiles. Those long draped vests and rotund fur hats, essential protection against cold mountain air, are trademarks of the traditional Vlach wardrobe, evidence of lives working the land and enduring its elements.

Vlachi have become synonymous with practical magic in popular culture, both locally and internationally. They hold a unique place in Serbian culture, despite being a mere 23K population in a nation of over 7 million. They were a part of the Serbian nation’s founding charter, and found themselves at home in Eastern Serbia 8 centuries later, even after lots of border fluctuations. Few today divinate or devote their working lives to herding livestock, but they have a culture that testifies to the spirit of survival. And their story is one in the fascinating anthology brought to us by this unique region of the world!