Saints, Songs & (Hi)Stories: Encountering Serbia's Vidovdan

A legendary martyr, a medieval battle, and much more...

It has been 10-months since we stepped off the American Ride (RIP Toby Keith) and moved to Serbia. Here early summer is a tempestuous season, with humid days, scattered lightning, and impromptu storms. ⛈️ The cluster of fall/winter holidays are a ways off, but in June we got to celebrate our first Vidovdan (St. Vitus’ Day) on the 28th.

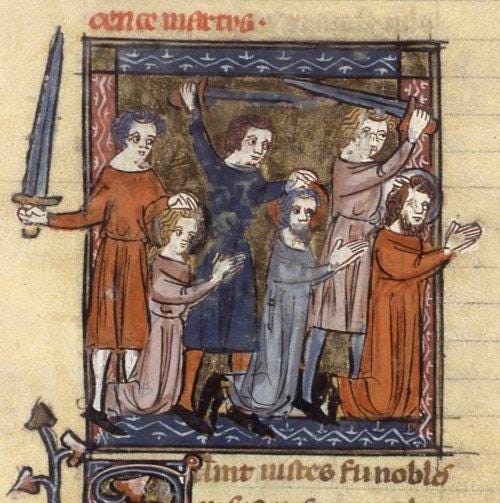

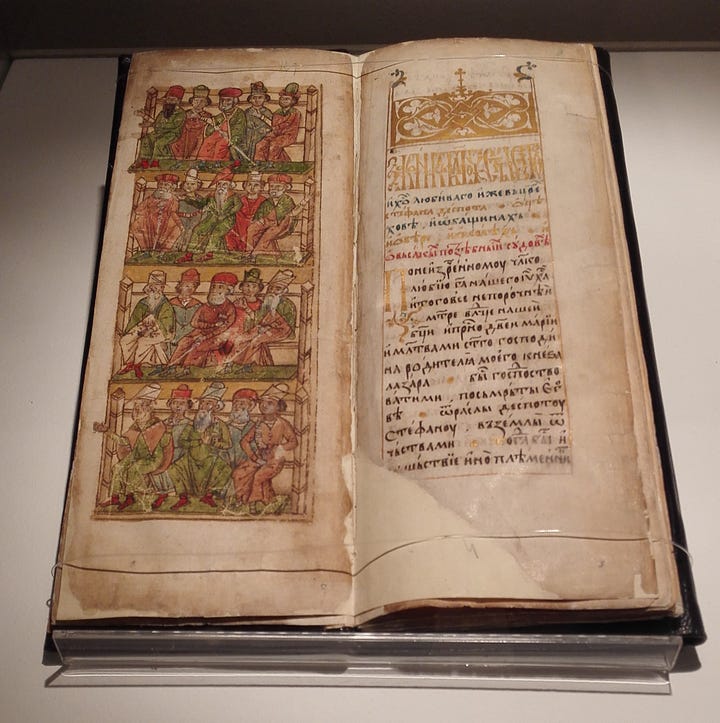

Saints days were not something I grew up with, but the local calendar is chock-full of them. The figure of St. Vitus was born on the island of Sicily c. 290 CE and died around his 13th birthday, killed during the (Roman) Emperor Diocletian’s persecution of Christians. The name “Vitus” (or some variant of it) appears in the text known as the Martyrologium Hieronymianum, dated c. 392 CE. Dramatic stories of stalwart faith and gruesome execution developed using Vitus’ name and personality from the 5th through the 7th centuries CE as his cult gained popularity, yet no specifics of his life or death were contemporarily recorded.

St. Vitus and the Slavs

As the Slavic peoples were being Christianized, the sainted Vitus was honored on June 15th as per the Julian calendar. When the Western Church adopted the Gregorian calendar, St. Vitus’ Day was aligned to the date of June 28th. He is honored on the 28th in Serbia, despite Serbia’s adherence the Julian calendar for (almost all other) holy days. The weeks leading up to St. Vitus’ Day coincided with the celebrations of the pre-Christian lightning deity, Svetovid. The popularity of St. Vitus’ Day was built from existing pagan traditions familiar to early Slavic catechumens, with lightning featuring in both the Christian and pagan versions of the holiday. ⚡️

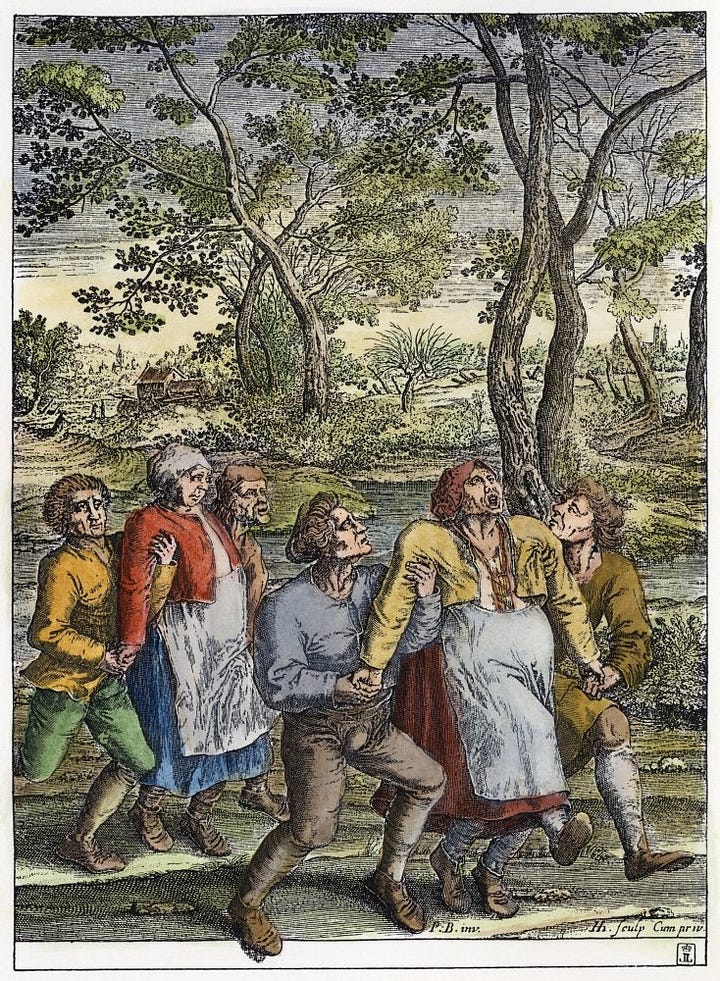

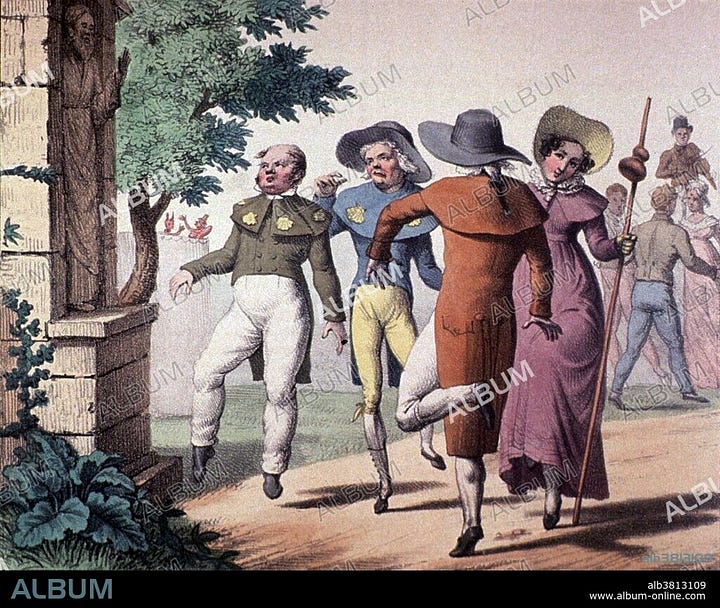

In Western Europe, this solstitial period ☀️ was marked by festivals involving dancing around St. Vitus statues, as he was designated the patron of dancers and entertainers. Devotion to Vitus was also associated with the neurological illness of rheumatic chorea, since patients with this condition suffer from spasms that mimic the motions of dancing. A member of the Catholic Fourteen Holy Helpers, St. Vitus was also called upon to guard against oversleeping (I can relate!), epilepsy, and of course, lightning strikes. During 18th century, St. Vitus gained Protestant associations, namely from members of the Methodist denomination who named St. Vitus the patron of their charitable drives.

Back to the Balkans

Quite a few moments before Methodism emerged, St. Vitus was known in the Balkans as Sveti Vid, with his day of honor Vidovdan. The Serbs and Bulgarians were absorbed into the Byzantine Commonwealth, adopting the faith of the Eastern Roman Empire. Serbia’s medieval rulers built churches and monasteries in the eastern fashion, adopting devotion to existing saints (including St. Vitus) as they built a state with an autocephalous church (est. 1219) bordered by the Dinaric Alps, Adriatic Sea, Aegean Sea, and Danube River.

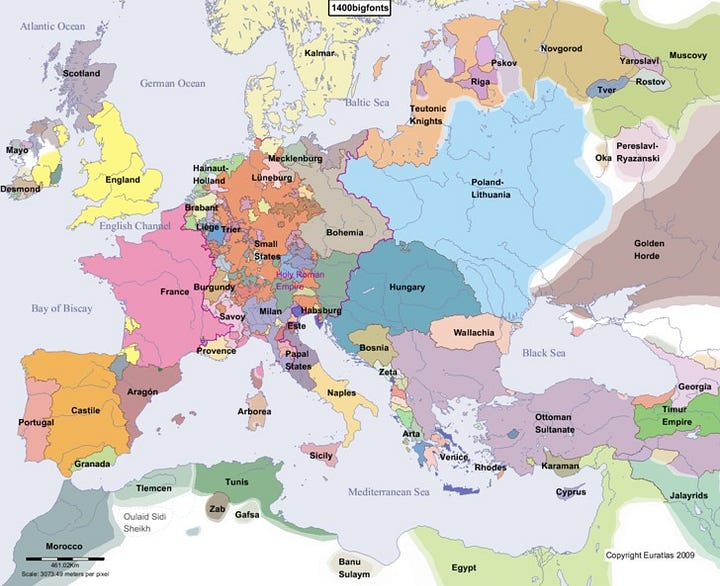

By the 14th century, Byzantium was contracting, and its client states to the northwest faced attacks by the Ottoman Turks. The Turks adopted Islam (conversion occurred from the 8-11th centuries CE), placing them in civilization conflict with “Christendom,” split between the Roman and Constantinopolitan spheres of influence as of 1054. By 1354, the Ottomans seized control of the Thracian peninsula, establishing a capital in the historical city of Adrianople (Edirne in Turkish). As of the 1330s, Serbia had expanded its territory to the shores of the Aegean Sea, putting it border to border with the Asian power eyeing the European continent.

Battlegrounds

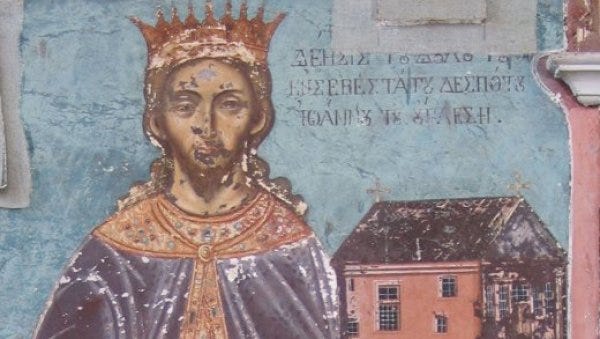

With a nemesis on his kingdom’s borders, Jovan Uglješa of the Mrnjavčević noble family galvanized forces for inevitable military confrontation. Uglješa held the title of despot, a member of the noble class with specific distinction granted by a ruling emperor. In this case, that distinction was granted by Emperor Stefan Uroš V. Uglješa’s brother Vukasin acted as co-ruler alongside Emperor Stefan, and supported his brother’s initiative when the former failed to gain support from other members of Serbia’s leading families. In the absence of adequate support from neighboring Bulgaria and what remained of Byzantium, the Brothers Mrnjavčević grouped their troops and marched towards Thrace when they caught word that a number of Ottoman troops were being rerouted to Anatolia. With a reduction of Ottoman troops on the Thracian peninsula, Serbian chances of pushing the remaining Thracian Ottomans back across the Bosporus looked promising, so it was time to act.

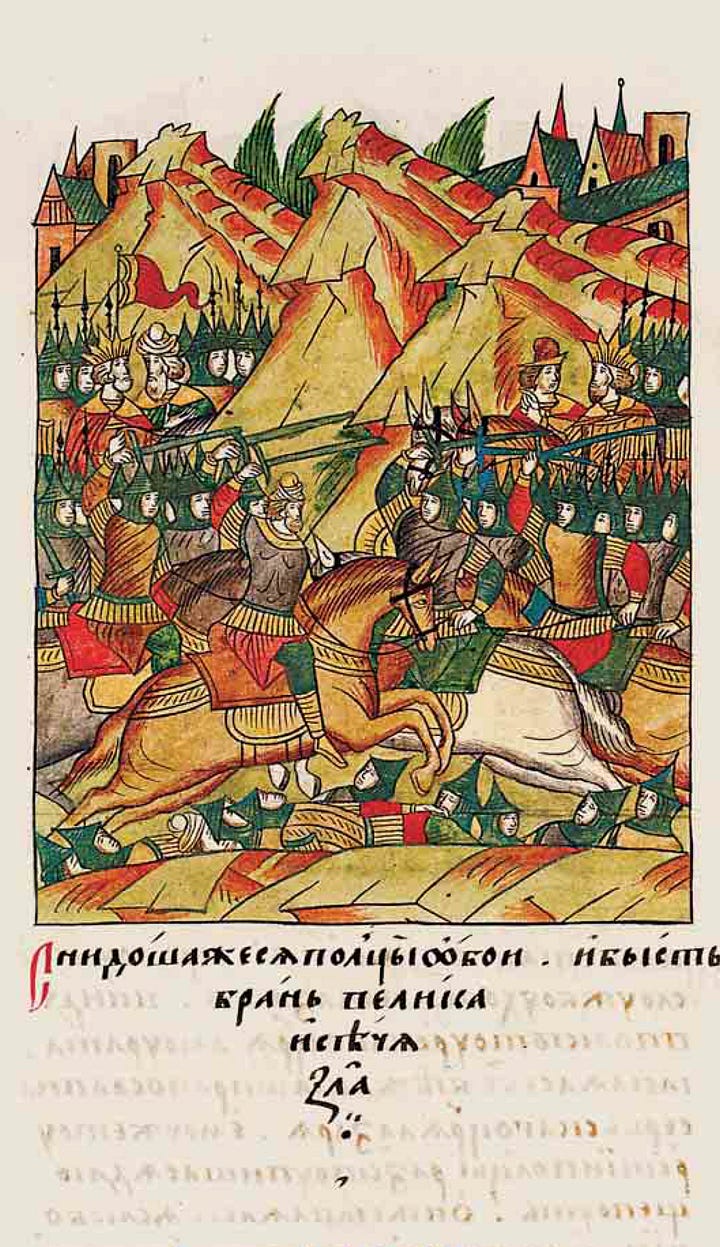

Sources count the Serbian forces standing between 50-70,000 men, with Ottoman defenses numbering a mere 4000 at most. As the Serbian troops camped near the banks of the Maritsa River on the night of September 26th, alcoholic beverages were imbibed, leading to mass drunkenness. It was on this evening of indulgence that Serbian forces ambushed by forces led by the Ottoman commanders Paşha Şâhin and Gazi Evrenos. In attempts to flee, thousands of Serbian troops drowned in the waters of the Maritsa, while stragglers bled out from Ottoman-inflicted wounds. Both Brothers Mrnjavčević died in battle, and the massive loss of Serbian forces left this strategic corner of Europe vulnerable to Ottoman expansion.

The Ottoman forces achieved a swift, bloody victory at Maritsa, and the year 1371 ended with Stefan Uroš V’s death without issue. The disastrous loss at Maritsa and the loss of Serbia’s reigning monarch prompted Knez (Prince) Lazar Hrebeljanović, ruler of the Serbian lands bordering Hungary, to focus defensive attentions southwards. Over the next eighteen years, the Ottomans continued their push north, conquering Byzantine, Bulgarian, and Serbian land as the Serbian nobles and their neighboring kingdoms struggled for unity in the face of a common enemy.

As summer 1389 approached, another monumental battle would upend the political dynamics of Southeastern Europe when, on the eighteenth St. Vitus’ Day following the fateful Battle of Maritsa.

1389

Like many celebrations, Vidovdan connects religious traditions, history, and cultural identity. The holiday itself became a part of Serbian observance following Christianization under the tutelage of the Byzantine Empire, and took on an exceptional historical significance during the medieval era when Kosovo Polje, a core region of the fourteenth century Serbian Empire, hosted a battle that had major geopolitical repercussions across Europe and Eastern Mediterranean. Nearly two decades after the Serbian defeat at Maritsa, the Serbian nobility remained fractured while the Ottoman Sultan Murad I moved his army into the core of Bulgaria. As the Ottomans marched towards Serbia through Macedonia, Prince Lazar began to organize the Serbian defenses. By the middle of June, the Ottoman forces arrived in Priština, while Lazar gathered forces near Niš. Primary records of these movements are scarce, but historians estimate that Lazar led up to 20K men, while Murad’s maximum number was around 30K. On June 15th (28th by the Gregorian calendar), the charge of the cavalries began and Vidovdan would be tied to this monumental military confrontation.

In addition to Prince Lazar, the Serbian forces were supported by Vuk Branković, Lazar’s son-in-law; Vlatko Vuković, a nobleman from the province of Herzegovina (then ruled by Hungarian vassal Bosnian King Tvrtko I); Đurađ II Balšić, nobleman from Zeta; and Teodor II Muzaka, a nobleman of Greek origin from Epirus. These forces gathered in a field, known as Kosovo Polje, north of Priština. Cavalry, flanked by archers, were positioned to lead the charge. Sultan Murad was supported by his sons, Bayezid and Yakub; commanders Evrenoz and Pasha Yiğit Bey; archers and cavalrymen; plus a herd of camels the Ottomans believed would frighten their opponents. Battle accounts differ and for a battle with such immense regional repercussions, so many details remain vague.

Technically, the battle was a draw, albeit one with pyrrhic impact. Casualties were heavy on both sides, and both leaders, Lazar and Murad, died during the course of the battle. Another victim of the battle was Miloš Obilić, a famed Serbian knight. Legends surrounding how the sultan was killed circulated in the century following the battle. By some accounts, Obilić is identified as the assassin who took down Sultan Murad I via sword. This narrative was nurtured through epic poetry crediting Obilić as the slayer of the enemy Sultan. Notice of the battle’s outcome spread across Europe, with word of the Sultan’s death prompting celebrations in Paris and Florence.

Vuković, sent by Tvrtko I, survived the battle, leading a correspondence between Tvrtko and his Italian city-state allies. A response letter to Tvrtko from the Florentines dated October 20th, 1389, praises the Serbian forces as heroic martyrs, noting that one of the twelve Serbian knights on the field at Kosovo (not named, but presumed by many to be Obilić) dealt a fatal blow to the Sultan. Branković also made it out alive, leading to speculation that he betrayed the cause by holding back his forces thinking the Serbs could not strike a clear victory. Branković later joined forces with Hungary to push back the Ottomans, but ended up being captured and dying as an Ottoman prisoner. Hungary, fearful of Ottoman expansion towards their borders, pushed to fortify their border with the remaining Serbian kingdoms along the Danube River.

Lazar was succeeded by his minor son Stefan Lazarević and widow Milica. Stefan and Milica were attacked by Hungarian King Sigismund in 1390, forcing them to accept Ottoman suzerainty. Lazarević acclimated to his role as an Ottoman vassal, which allowed him to accumulate lands at the expense of other Serbian nobles, who continued to push back against Ottoman expansion, forfeiting land and life in the course resistance.

The remains of Serbia’s medieval empire crashed in 1459 when Smederevo, a riverside fortress complex built by Vuk’s son, Đurađ Branković, was captured. Like the life of St. Vitus (Sveti Vid), the life of the Battle of Kosovo developed many associated myths, yet this battle, despite murky details, marked a massive geopolitical power shift in Southeastern Europe. The next two centuries of Central European history would be dominated by Ottoman attempts to breech the lines of Serbian, Hungarian, Austrian, Wallachian, and Polish defenses to enter the core of Europe, leaving the Balkan peninsula in the unenviable position of chaotic frontier on the borderlands of competing powers.

Songs 🎼 Dance

Serbia remembers the Battle of Kosovo on June 28th, as well as a slew of other historical events related to Serbian/Balkan history. On Vidovdan 1876, the Serbs symbolically and literally declared their fight for independence against the Ottomans; a Serbian-Austrian alliance was signed in 1881; Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand that day in 1914 and exactly five years on, the Treaty of Versailles was signed; 1921 marked the approval of the Vidovdan Constitution for the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes; Vidovdan 1948 saw Yugoslavia move to distance itself from the Soviet Union. Outside of Serbia, Vidovdan has been declared an official holiday in the city of Chicago, thanks to its Serbian diaspora community. We attended local fair in neighboring Sremska Mitrovica, which featured live music and folkloric dancing troops representing different styles of kolo from across northern Serbia performing against the backdrop of the ruins of the Roman grain market.

What I loved about how this holiday is celebrated is that graduation ceremonies for different levels and types of schooling are scheduled for Vidovdan, giving communities the opportunity to honor high achieving youth. In Sremska Mitrovica, music school students were honored in the course of the performances, with particular acknowledgement for one young clarinetist invited to study at a conservatory in Vienna, Austria.

Even the youngest scholars receive acknowledgement, like second-grade star Dimitrije, who received a cash prize from the city of Šabac for his classwork and development as a pianist. 🎹 💫

There’s a lot of past trauma associated with this day of the year, but seeing Vidovdan celebrated with music, dance, and children’s successes made it a time for welcoming the future as well as honoring the past. Feeling the rhythm and mimicking steps connecting them to the generations who endured harsher St. Vitus’ Days, even the youngest joined the celebrations from the sidelines. Lighting can strike at any time, but every season calls for some music and dance, especially for the patron saint of these timeless joys!

Go Dmitrije!